Jugend v. J.Wiesheu Mbg. - Geschichten_en_v3

Main menu

Jugend v. J.Wiesheu Mbg.

Historical Memories from my Youth and School from 1936-

Before the government reform of 1972, my hometown of Schweinersdorf was a municipality with a parish church, a school and school office, and four farms. The elementary school address was #1, and was located at the southern end of the village. At the age of 6, I began first grade at the elementary school at Eastertime. There were two classrooms at the school: students from grades 1-

From my early school days I have the following memory: The teacher asked me to accompany a classmate, Maria Furtner, who lived in Altfalterbach, part way home. We both went only to the edge of the forrest, where there was a large oak tree. We collected some acorns and sat down and played with them.

in the front: Schweinersdorf [GWS30]

in the background: Altfalterbach.

Find the oak in between

Meanwhile, kids from the ''big school'' came and took Maria to Altfalterbach with them. The following night I had a strange dream about this place. I looked up at the sky behind Schweinersdorf. From the clouds, a bright spot appeared, with huge crossed beams. I can still see this vision in front of me.

2 nd form of the „little school"

front row (l.t.r.): Barbara Sixt, Kathi Frey, Josef Wiesheu (Schweinersdorf), Maria Schwanghart, Therese Zauner

back row (l.t.r.): Ursula Baumgartner, Josef Wiesheu (Inzkofen), Barbara Aneser [JWM36]

In second grade, the ''small school'' got a new teacher. Her name was Toni Bader. As an altarboy, I saw her every morning and in the choir stall at school worship.

My father was an opponent of the Nazi regime during the Third Reich. Adoph Hitler, of the NSDAP, came to power on Jan. 30, 1933. Members of that party organized the SA and from 1930, they integrated into Hitler's SS. The SA men wore brown uniforms, brown boots and a swastika armband. SS men had a black unform with the SS emblem on the collar lapel.

In 1933, an SA man, accompanied by a police officer, appeared at the family farm with a search warrant. A gun had allegedly been stolen by a former Huber (name of the farm) servant. The suspect stated that he wanted to stay with his former boss, but my father had bought the gun for him (the farm hand). The house was searched. The childrens' clothes were dumped from the drawers in the bedroom. They searched the laundry. No gun was ever found. They found no evidence for the crime.

Often, the SA men marched through our village to the beat of pipes and drums. We children heard the sounds, but were not allowed to go into the streets. Apparently, this was noticed by the neighbors. Membership in the Hitler Youth and the BDM was not for the Wiesheu children. Actually, it sounded quite exciting.

In 1938, my elder brother Sebastian, who had been missing since Stalingrad 1941/42, was once driving a load of straw and manure to the field. When the neighbor hoisted the swastika flag in support of an upcoming election, the flag fluttered in the wind and the horses shied from it. The load of manure was dumped into the street. My brother shouted, ''Because of your damned flag this is happening now!'' Because of this statement, my father had to apologise to the uniformed Ortsgruppenleiter Ludwig Fischer.

It was time for the Christmas tree sale at the Huber farm during the thirties. We children were allowed to ride to the market in Moosburg to deliver the pre-

Occasionally, the SA men went on horseback throughout the village. They wanted to take over one of my father's fields on the outskirts for their exercises. My father refused to allow their demand on the grounds that it was the field closest to his farm, and also a productive piece of land, to which he recieved the reply: ''We'll see, there are other ways for us to get the field.''

A document for imprisonment in the Dachau concentration camp was subsequently issued. It fell into the hands of a relative in a neighboring village, however, who had been a member of the Nazi party since 1923. He intervened and tore up the letter, saying, ''No way!''

For these so-

In the 5th grade, I went to the ''big school'' in the classroom next door, with teacher Georg Dietmar. He was a strict teacher, but we learned a lot from him. Because each of us two boys in the class was called Joseph Wiesheu, he called my cousin Wiesheu 2 and me, Wiesheu 1. For the last two years of the war, 1944-

From 1939-

About 25 prisioners were housed in the former stables of the parsonage. In September, 1939, at the outbreak of the war, the prisoners were primarily from Poland. From 1941 to 1945, when the war ended, they were French. Usually, a wounded soldier brought the prisioners to the farms to be used as laborers.

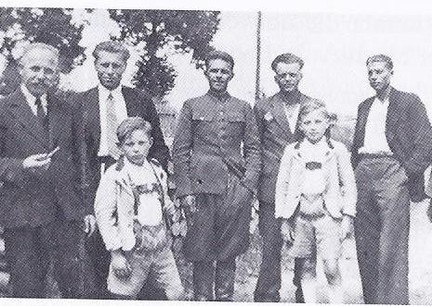

Wiesheu family and polish assistants; [JWM40]

The hands were treated well. They ate with us at the table and communication worked quite well, even in Bavarian slang. Occasionally on the farm, ''black'' slaughter of a pig took place (illegal butchering of an animal). Though the Frenchmen may have noticed, they remained silent.

Sometimes, the Frenchmen received packages from home via the Red Cross of Switzerland. These were distributed by St. John's Church in Moosburg. They often gave us boys dark chocolate. Sometimes it was slightly moldy. We scraped it off, and it tasted good, nonethless.

In the last years of the war, 1944-

My brother Georg was born in 1928. In 1945, he was called up for labor service. To be used for the defense of his country, he was sent to Austria. As the advance of the American army was getting much closer, the organized retreat of the troops disolved. Together with his friend, Simon Lösch from Mauern, they hid on a farm in Zell am See, Austria. From there, they went home on foot.

I was not drafted, but I received three days of training near Freising. The sharp-

At about 5pm on the day before May 1, 1945, a German military vehicle, with about 25 seventeen year-

Written down in November, 2012 by Josef Wiesheu (*1929), Moosburg

Translation by Maximilian Grötsch and Peggy Chong

e10010_SI_Memories_from_my_Youth_en_03Jun14_revjar